MSTrIPES (Monitoring System for Tigers: Intensive Protection and Ecological Status)

Currently the tiger reserves carry out law enforcement and ecological monitoring activities at regular interval, but the information generated is ad hoc and is rarely available to the tiger reserve managers in a format for informed decision making in an adaptive management framework. The “M-STrIPES” has been designed to addresses this void.It is a platform where modern technology is used to assist effective patrolling, assess ecological status and mitigate human-wildlife conflict in and around tiger reserves.

The MSTrIPES program uses Global Positioning System (GPS), General Packet Radio Services (GPRS), and remote sensing, to collect information from the field, create a database using modern Information Technology (IT) based tools, analyses the information using GIS and statistical tools to provide inferences that allow tiger reserve managers to better manage their wildlife resources.

Patrol module

The patrol module maintains a spatial database of patrol track logs, crime scenes with geotagged photographs and important observations made by field staff while on different types of patrol duties. The phone app allows visualization of all patrols in real time across the country when in cellular network connectivity. It also permits the guard to send geotagged location data to specified phone numbers in case of emergency (SOS) function. The mobile app can continue to operate in areas without phone network by using the phone’s inbuilt GPS and preloaded base maps.

Ecological Module

The tiger reserves of India use a set of standardized protocols for ecological monitoring by field staff which include the following components:

1) Occupancy of carnivores and large ungulates,

2) Abundance estimation of ungulates,

3) Assessment of anthropogenic impacts and

4) Habitat assessment.

The ecological monitoring comprising of above components are implemented across the country at a spatial resolution of 20 square km every four years and twice annually within all tiger reserves and these standardized protocols are now part of ‘Ecological Module’ of MSTrIPES program.

Conflict Module

The conflict module of MSTrIPES addresses data recording, achieving, geotagging, and spatial analysis of human-wildlife conflict details. The app has provision for recording the details of attacks on humans, attacks on livestock, crop damage and property damage. This information on location, with spatially referenced photo-evidence, and extent of conflict allows wildlife managers to mitigate conflict with appropriate interventions.

India has a Memorandum of Understanding with Nepal on controlling trans-boundary illegal trade in wildlife and conservation, apart from a protocol on tiger conservation with China.

A Global Tiger Forum of Tiger Range Countries has been created for addressing international issues related to tiger conservation.

During the 14th meeting of the Conference of Parties to CITES, which was held from 3rd to 15th June, 2007 at The Hague, India introduced a resolution along with China, Nepal and the Russian Federation, with directions to Parties with operations breeding tigers on a commercial scale, for restricting such captive populations to a level supportive only to conserving wild tigers. The resolution was adopted as a decision with minor amendments. Further, India made an intervention appealing to China to phase out tiger farming, and eliminate stockpiles of Asian big cats body parts and derivatives. The importance of continuing the ban on trade of body parts of tigers was emphasized.

Based on India’s strong intervention during the 58th meeting of the Standing Committee of the CITES at Geneva from 6th to 10th July, 2009, the CITES Secretariat issued notification to Parties for submitting reports relating to compliance of Decisions 14.69 and 14.65 within 90 days with effect from 20.10.2009 (Progress made on restricting captive breeding operations of tigers etc.). During the 15th meeting of the Conference of Parties, India intervened for retaining the Decision 14.69 dealing with operations breeding tigers on a commercial scale.

Management Effectiveness Evaluation

Survival of tigers is dependent on conservation and management efforts. To gauge the success of conservation efforts as well as to guide management inputs, it is important to assess the effectiveness of management of Tiger Reserves.

Post the disappearance of tigers in Sariska Tiger Reserve, the Government of India issued a directive to the Office of Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG) of India and the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC), Government of India to conduct an independent audit and place the report in the Parliament.

The Wildlife Institute of India (WII) in close collaboration with global experts and National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) developed a framework for independent evaluation procedure to evaluate Tiger Reserves of the country. MEE Framework includes consideration of design issues, the adequacy and appropriateness of management systems and processes and the delivery of protected area objectives including conservation of values.

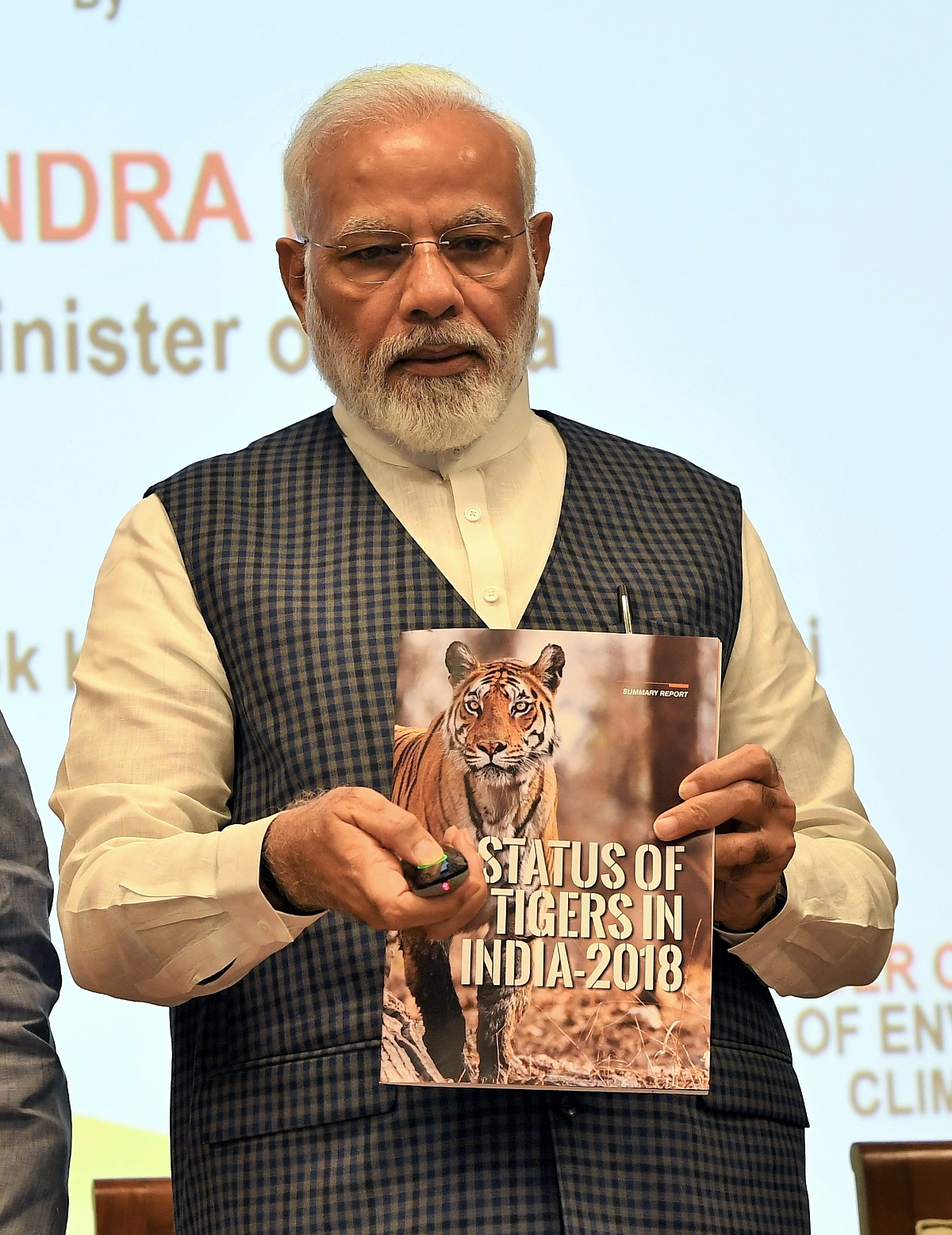

(Honourable Prime Minister of India releasing MEE report -2018 at New Delhi)

India is among the select countries in the world that have institutionalized the MEE Process. India made a beginning in evaluating the management effectiveness of its world heritage sites, national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and Tiger Reserves in 2006.Four repeat cycles of evaluation of Tiger Reserves Network have been made after every four years from 2006 to 2018 in India. This process is the most significant approach for tiger conservation and associated landscape connectivity conservation and management.

For more information on MEE, the details of past evaluation exercises and the reports, please visit the ‘Report‘ section of this website.

Counting tigers in India

Tigers are a conservation dependent species. Major threats to tigers are poaching that is driven by an illegal international demand for tiger parts and products, depletion of tiger prey, and habitat loss due to the ever increasing demand for forested lands. To gauge the success of conservation efforts as well as to have a finger on the pulse of tiger populations and their ecosystems, the National Tiger Conservation Authority in collaboration with the State Forest Departments, the Wildlife Institute of India and conservation partners conducts a National assessment for the “Status of Tigers, Co-predators, Prey and their Habitat” once inevery four years. The methodology used for this assessment was approved by the Tiger Task Force in 2005. The first assessment based on this scientific methodology was done in 2006 and subsequently in 2010, 2014 and 2018.

In 2006, the tiger population was estimated at 1,411 (1,165 to 1,657) which was much lower than the earlier official estimates. This brought about major changes in tiger conservation policy, legislation, and management. Special stress was laid on village relocation from core/critical tiger habitats and enhancing protection by creating the Special Tiger Protection Force. Subsequently, these concerted actions resulted in an upward trend in the tiger population as documented by the 2010 population estimates of 1,706.

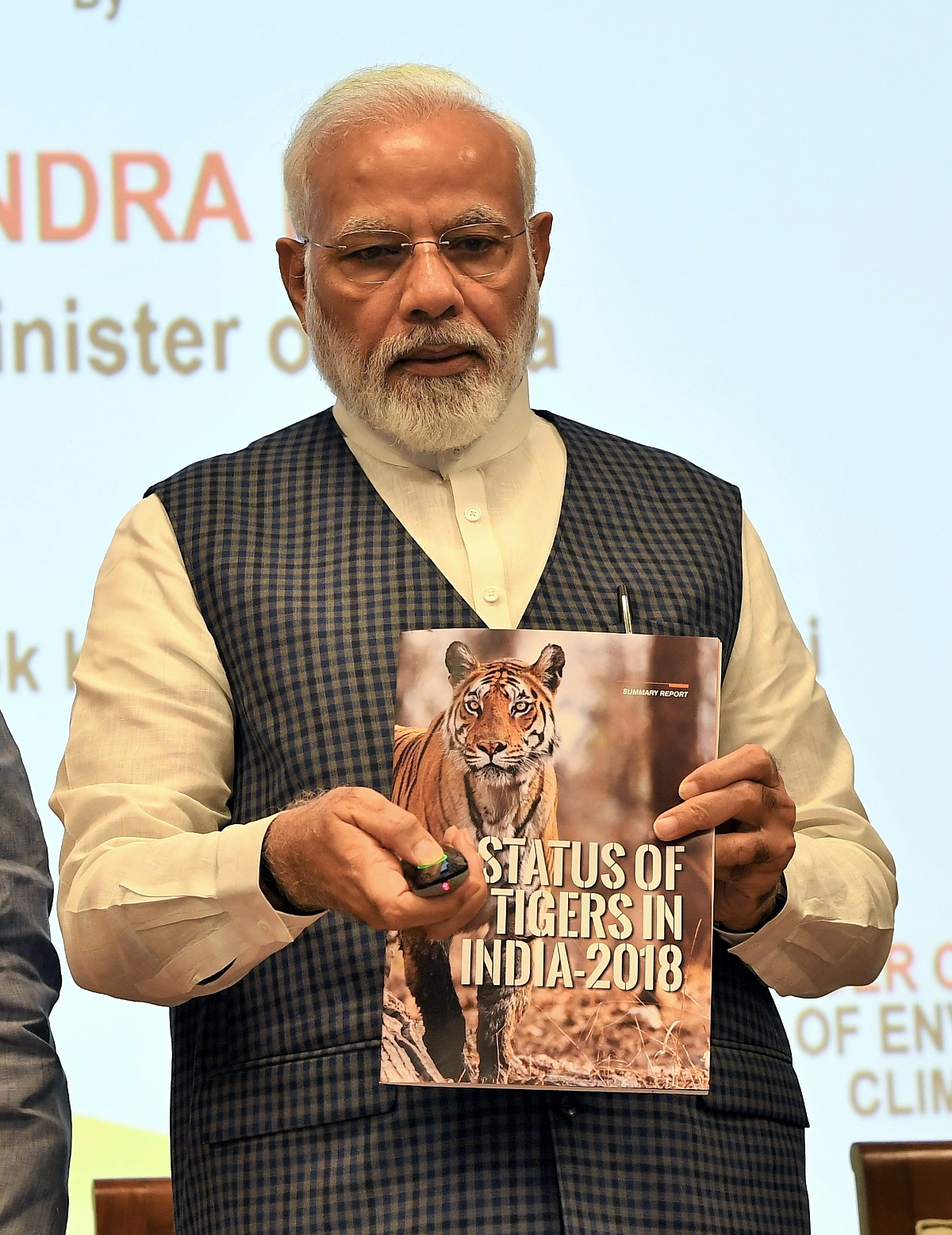

(Honourable Prime Minister of India releasing the report ‘Status of Tigers in India – 2018‘ on the occasion of Global Tiger Day at New Delhi, India).

However, the 2010 assessment also showed a decline in tiger occupied area. This decline in tiger occupancy was recorded in areas outside of tiger reserves, indicating loss of habitat quality and extent – a crucial element essential for maintaining genetic connectivity between individual tiger populations. To address this vital conservation concern, the NTCA in collaboration with the WII delineated the minimal tiger habitat corridors connecting tiger reserves for implementing landscape scale tiger conservation. Now all tiger reserves manage their tiger populations based on a tiger conservation plan (TCP), which addresses specific prescriptions for core, buffer, and corridor habitats.

The 2014 assessment, further bore testimony to the inputs provided by Project Tiger and based on the double sampling approach, showed a 30% increase over the previous cycle. India now has 70 % of the global tiger population at 2226. 1540 distinct camera trapped photographs of tigers have been obtained and the rest based on sound statistically robust, spatially explicit capture recapture (SECR) models.

The fourth cycle of National tiger status assessment of 2018-19 is the most accurate survey conducted. The survey covered 381,400 km 2 of forested habitats in 20 tiger occupied states of India. A foot survey of 522,996 km was done for carnivore signs and prey abundance estimation. In these forests, 317,958 habitat plots were sampled for vegetation, human impacts and prey dung.

Camera traps were deployed at 26,838 locations. These cameras resulted in 34,858,623 photographs of wildlife of which 76,651 were of tigers and 51,777 were of leopards. The total area sampled by camera traps was 121,337 km 2 . The total effort invested in the survey was 593,882 man-days. We believe that this is the world’s largest effort invested in any wildlife survey till date, on all of the above criteria.

A total of 2,461 individual tigers (>1 year of age) were photo-captured. The overall tiger population in India was estimated at 2,967 (SE range 2,603 to 3,346). Out of this, 83% were actually camera trapped individual tigers and 87% were accounted for by camera-trap based capture-mark-recapture and remaining 13% estimated through covariate based models. Tigers were observed to be increasing at a rate of 6% per annum in India when consistently sampled areas were compared from 2006 to 2018. Tiger occupancy was found to be stable at 88,985 km 2 the country scale since 2014 (88,558 km 2 ). Though there were losses and gains at individual landscapes and state scales.

For further details and past tiger monitoring reports, please refer to the estimation reports given in the side link above. For all other reports, please visit Reports‘ section of this website.

As a part of active management to rebuild Sariska and Panna Tiger Reserves where tigers have become locally extinct, reintroduction of tigers / tigresses have been done.

Special advisories issued for in-situ build up of prey base and tiger population through active management in tiger reserves having low population status of tiger and its prey.

Realizing the importance of ‘tiger protection’ in biodiversity conservation, the Finance Minister had announced policy initiatives on 29th February, 2008, for constituting ‘Special Tiger Protection Force’ (STPF).

Based on the one time grant of Rs. 50 crore provided to the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) for raising, arming and deploying a Special Tiger Protection Force, the proposal for the said force has been approved by the competent authority for 13 tiger reserves.

The STPF has been made operational in the States of Karnataka (Bandipur), Maharashtra (Pench, Tadoba-Andhari, Nawegaon-Nagzira, Melghat), Rajasthan (Ranthambhore), Odisha (Similipal) and Assam (Kaziranga), out of 13 initially selected tiger reserves, with 60% central assistance under the ongoing Centrally Sponsored Scheme of Project Tiger (CSS-PT).

There are two options available for constituting the STPF: one is ‘Forest Option’ and another one is ‘Police Option’.

Keeping in view of the duties to be performed by the personnel of STPF, a syllabus covering subjects such as wildlife conservation, protection, forest and wildlife law among others has been prescribed.

The STPF syllabus may be downloaded here.

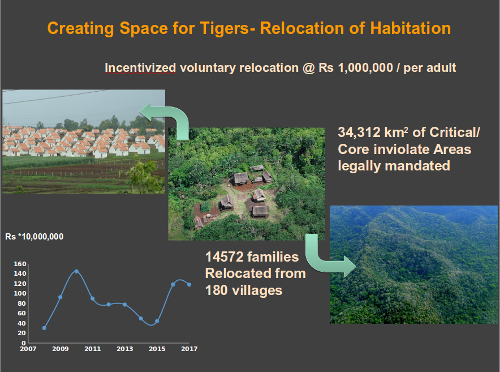

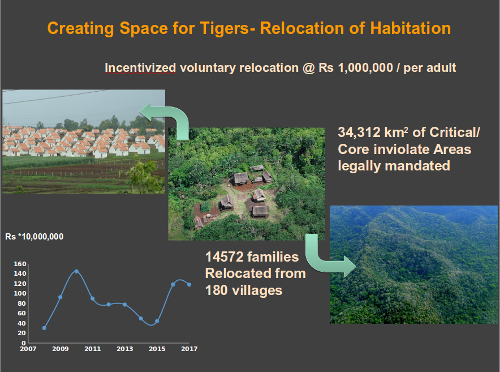

Why relocation?

Available data and research findings on tiger ecology indicate that for maintaining a viable population of 80-200 tigers in a tiger reserve, a minimum of 800 – 1000 sq km of inviolate forest area is required.

Tiger being an “umbrella species”, the protection offered to it also ensures viable populations of other wild animals (co-predators, prey) and forest, thereby facilitating the ecological viability of the entire forest area / habitat. Therefore, keeping the core area of a tiger reserve becomes becomes an ecological imperative for the survival of source populations of tiger and other wild animals.

Legal provisions

The Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972, as well as the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, require that rights of people (Scheduled Tribes and other traditional forest dwellers) recognized in forest areas within core/critical tiger/wildlife habitats of tiger reserves/protected areas and after recognition the rights may be modified and resettled for providing inviolate spaces to tiger/wild animals.

The chapter IV of the Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972 (Section 24) provides for acquisition of rights in or over the land declared by the State Government under Section 18 (for constituting a Sanctuary) or Section 35 (for constituting a National Park).Further, the sub-section 2 of Section 24 of the Wild Life (Protection) Act, authorizes the Collector to acquire such land or rights. Therefore, payment of compensation for the immovable property of people forms part of modifying / settling their rights which is a statutory requirement.

Relocation package

The new package for village relocation/rehabilitation which covers the provisions of “National Rehabilitation and Resettlement Policy, 2007” has been designed taking into consideration the difficulties / imperatives involved in relocating people living in forest areas:

The proposed package has two options:

Option I – Payment of the entire package amount (Rs. 10 lakhs per family) to the family in case the family opts so, without involving any rehabilitation / relocation process by the Forest Department.

Option II – Carrying out relocation / rehabilitation of village from protected area / tiger reserve by the Forest Department.

In case of option I, a monitoring process involving the District Magistrate of concerned District(s) would be ensured so that the villagers rehabilitate themselves with the package money provided to them.

In this regard, a mechanism involving handholding, preferably by external agencies should also be ensured, while depositing a considerable portion of the amount in the name of the beneficiary in a nationalized bank for obtaining income through interest generated.

In case of option II, the following package (per family) is proposed, at the rate of Rs. 10 lakhs per family:

(a) Agriculture land procurement (2 hectare) and development : 35% of the total package

(b) Settlement of rights : 30% of the total package

(c) Homestead land and house construction : 20% of the total package

(d) Incentive : 5% of the total package

(e) Community facilities commuted by the family (access road, irrigation, drinking water, sanitation, electricity, telecommunication, community center, religious places of worship, burial/cremation ground) : 10% of the total package.

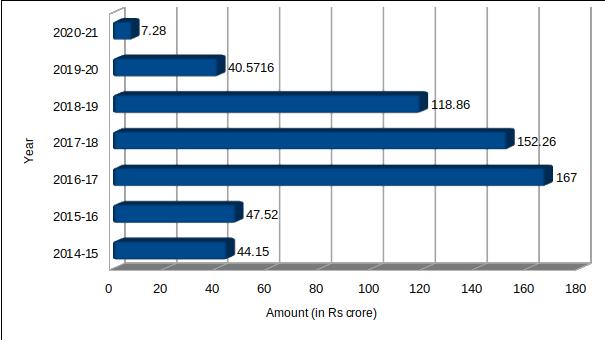

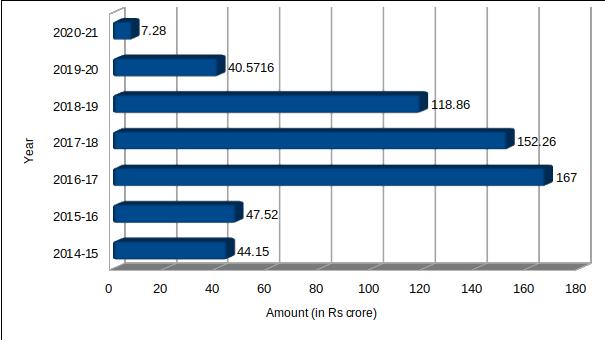

Funds utilized for Village Relocation

For implementing voluntary village relocation program, so far Rs 577.64 crores has been spent for the period 2014-15 to 2020-21. The year wise fund utilization details are given below:

Monitoring Village Relocation

The relocation process would be monitored / implemented by the following two

Committees:

State level Monitoring Committee

(a) Chief Secretary of the State – Chairman

(b) Secretaries of related departments – Members

(c) State Principal Chief Conservator of Forests- Member

(d) Non-official members of respective – Members

Tiger Conservation Foundation

(e) Chief Wildlife Warden – Member-Secretary

District level Implementing Committee

This committee comprises of the following members and its main objective apart from implementing the relocation is to ensure convergence of other sectors for fulfilling the developmental needs of communities.

(a) District Collector – Chairman

(b) CEO – Member

(c) Representative officials from: – Members PWD, Social Welfare, Tribal

Department, Health Department, Agriculture Department, Education Department,

Power and Irrigation Departments

(d) Deputy Director of the Tiger Reserve/PA – Member Secretary

For more information on voluntary village relocation, you may refer “Format for preparation fo village relocation plan from core / critical tiger habitat” document under ‘Document ->Guidelines-> All Advisories’ section.